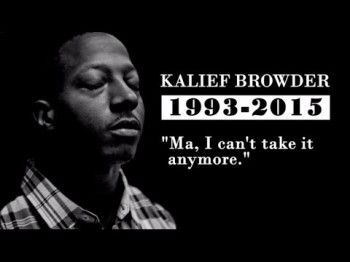

The Story of Kalief Browder

By Francesca Sands, Juvenile Justice Fellow

Based on excerpts from interviews of Kalief Browder conducted by Jennifer Gonnerman.

In 2010, sixteen year-old Kalief Browder of the Bronx was arrested for allegedly stealing a backpack. He was charged with robbery and assault, but he said he didn’t commit the crime. Still, he was imprisoned at Rikers Island to await his trial…for three years. Kalief sat and waited while his life went by. Most of this time was spent in solitary confinement. He used a vent in the cell to communicate with other inmates through the walls, which offered some solace, expect for the frequent times he heard head banging, wall kicking, or distressed screaming from his neighbors at any hour of the day or night.

The only education offered to teens like Kalief in solitary is Cell Study, which is when an officer slips a worksheet under the cell door for completion, and then picks it up a few days later. Despite playing around in the hallways with friends, flirting with girls by their lockers, and doing what other young teens do, Kalief had always taken school seriously. But whatever scholastic promise he held before Rikers was disregarded within the prison’s confines, and Kalief missed out on his junior and senior years of high school.

Kalief endured violence from guards and other inmates, but he felt that the psychological and emotional trauma caused by his circumstances was worse. He was hungry all the time. The guards would sometimes skip over his cell when delivering meals, let alone ever give him the few pieces of leftover bread they always had. He was constantly stressed out. If he ever needed to communicate with the guards, the only way to get their attention was to quickly stick his arm through the slot in the door when it opened briefly for passing in meal trays. If he didn’t “hold his slot,” as they call it, he was subjected to various forms of mistreatment and disrespect such as no showers or no food. He was entirely helpless.

Still just a boy, Kalief was naturally accustomed to and dependent on asking his mother for help when he found himself in tough situations. But all his mother could do in this situation was cry on the phone. He attempted suicide after about two years at Rikers. Every so often, Kalief would get called to stand before a judge to hear whether he would get his trial. During one such meeting, Kalief was offered release only if he pleaded guilty. Despite wanting more than anything to go home, he turned down the deal, guided by his moral grit that prevented him from admitting to a crime he didn’t commit. And he was well aware that if he ever got the trial he was hoping for, he could face up to 15 years in state prison if he lost.

In the spring of 2013, the judge dropped all the charges against Kalief and he finally went home. He enrolled in a GED class, and passed his GED exam about a year later. He then enrolled at Bronx Community College, where he did well, but his mental health problems resulting from his time at Rikers formed insurmountable obstacles. After more suicide attempts and visits to hospital psychiatric wards, Kalief ended his life in June of 2015 at the age of 22.

As we remember the life and struggle of Kalief Browder this month, the reality of incarceration-induced mental illness continues to affect youth everywhere. In a report by the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, a longitudinal study reveals that nearly 50 percent of male juveniles and nearly 30 percent of female juveniles had at least one psychiatric disorder five years after their initial, baseline interviews for the study, which were conducted while they were awaiting adjudication of their cases. Substance abuse and disruptive behavior disorders were found to be the most common, and with additional long-term gender and race-related effects that put some groups at significant mental and social disadvantages, the need for more age-appropriate criminal justice is apparent.

At no point during or after Kalief Browder’s trial did anyone in power apologize to him or even acknowledge that he lost three years of his life, the rest of his youth, and ultimately his will to live, in solitary confinement at Rikers Island.