JJDPA Matters: A Look at the Latest Data on Race and Juvenile Justice

Josh Rovner is the State Advocacy Associate for the Sentencing Project, where he focuses on juvenile justice issues.

This post is part of the JJDPA Matters blog, a project of the Act4JJ Campaign with help from SparkAction. The JJDPA, the nation's landmark juvenile justice law, turns 40 this September. Each month leading up to this anniversary, Act4JJ member organizations and allies will post blogs on issues related to the JJDPA. To learn more and take action in support of JJDPA, visit the Act4JJ JJDPA Matters Action Center, powered by SparkAction.

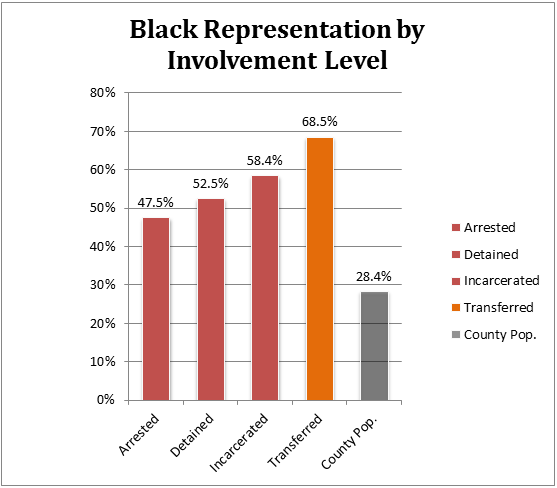

The remarkable drop in juvenile arrest rates since the mid-1990s has done little to mitigate the gap between how frequently black and white teenagers encounter the juvenile justice system. These racial disparities threaten the credibility of a justice system that purports to treat everyone equitably.

Across the country, juvenile justice systems are marked by disparate racial outcomes at every stage of the process, starting with more frequent arrests for youth of color and ending with more frequent secure placement.

The Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act (JJDPA) of 1974 requires that data be collected at multiple points of contact: arrest, referral to court, diversion, secure detention, petition (i.e., charges filed), delinquent findings (i.e., guilt), probation, confinement in secure correctional facilities, and/or transfer to criminal/adult jurisdiction.

The Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act (JJDPA) of 1974 requires that data be collected at multiple points of contact: arrest, referral to court, diversion, secure detention, petition (i.e., charges filed), delinquent findings (i.e., guilt), probation, confinement in secure correctional facilities, and/or transfer to criminal/adult jurisdiction.Jurisdictions are also required to report the race of juveniles handled at each of these stages. As a result of this requirement—known as the Disproportionate Minority Contact (DMC) protection of the JJDPA—states have collected racial data on young people’s encounters with the justice system.

National data is now available from the Department of Justice, and the W. Haywood Burns Institute has organized the publicly available state-by-state data and county-by-county data.

Measuring DMC: The Relative Rate Index

The Relative Rate Index (RRI) measures the rate of racial disparity between white youth and youth of color at a particular stage in the system. The most recent RRI (2.1) among African-Americans at the point of arrest means that arrest is more than twice as common for black youth as for white youth.

The extent to which jurisdictions experience racial and ethnic disparities has been exhaustively studied. A 2002 literature review found that two-thirds of studies on minority overrepresentation in the criminal justice system showed negative race effectsat one or more steps of the process. DMC reflects both racial biases woven into the justice system and differences in the actual offending patterns among racial and ethnic groups. What is not in dispute is that the differences exist. OJJDP reports that disproportionate juvenile minority representation “is evident at nearly all contact points on the juvenile justice system continuum.”

The discrepancies do not end at arrest. Among those juveniles who are arrested, black youth are more likely than white youth to be referred to a juvenile court. They are more likely to be processed and less likely to be diverted into other consequences. Among those found guilty, they are also more likely to be sent to detention. Among those detained, black youths are more likely to be transferred to adult facilities. The disparities grow with every step.

Diving into the Numbers:

Status Offenses and Technical Violations

Status offenses are a category of behaviors that are illegal based solely on the age of the offender. Examples include violating curfew laws or skipping school. In 2011, African American youth were 269 percent more likely than their white counterparts to be arrested for violating curfew laws. The fluctuations in arrest rates for black and white youth alike suggest that policy changes, not actual behaviors, are driving the gaps.

Drug Arrests

Drug arrests also reveal vast racial gaps. At the beginning of the 1980s, black and white youth were arrested at roughly equivalent rates, approximately one in 300 (or 330 arrests per 100,000 youths). Between 1981 and 1989, arrest rates for African American youth increased by 383 percent even as arrests of white juveniles declined by 11 percent. As of 2011, black youth are still 44 percent more likely than white youth to be arrested for drug offenses.

Next Steps for a More Equitable System

Are youth of color committing more crime, thus resulting in a higher arrest rate? Comparing arrest rates to self-reported data for the most common offenses committed by juveniles shows that the answer is often “no.”

Many states have come a long way in their ability to collect and report race data. But it is well past time to move beyond the assessment phase and into a phase that endeavors to reduce racial and ethnic disparities.

To be eligible for funding under the JJDPA, the law merely requires that states “address” disparity. To date, regulations have not been issued to specify the necessary step states must take to comply with this mandate.

The JJDPA, enacted in 1974, is long overdue for a reauthorization—and in that process, we must strengthen the requirement that states report the steps they are taking or have taken to reduce DMC.